I’m off to New York next week to catch the tail-end of a major exhibition at the Guggenheim, Hilma af Klint: Art for the Future. The Swedish artist Hilma af Klint is virtually unknown and her work until very recently remained mostly unseen. This invisibility is in largest part due to her own wishes that her works not be shown publicly until at least 20 years after her death in 1944. She was creating spiritual art for a more enlightened humanity. Af Klint is now considered by many to be the first European abstractionist, based on the unprecedented abstract works she created in the early years of the 20th century, before Wassily Kandinsky created the works that have until now been considered to be the earliest in this vastly important historical genre.

The Spiritualist movement of the late 19th century influenced Western art forms deeply, and af Klint was a gifted medium, receiving visual and verbal transmissions from disembodied spiritual guides, the “High Masters” who directed her art. She was deeply interested in Theosophy and later Anthroposophy, and these ideas also greatly affected her conscious practice.

I was deeply struck by the few paintings I saw in reproduction that I encountered 30 years ago when some of her paintings were exhibited in the 1987 LACMA curated by Maurice Tuchman, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1885-1985, accompanied by the groundbreaking essay on af Klint by Åke Fant. The work ranges from figural abstraction suggesting the strong influence of Art Nouveau and associated schools of work in northern Europe at the end of the 19th century to fascinating biomorphic motifs to the purest geometric abstraction—and back again. Though the works manifest an evolving spiritual ethos which expresses a longing for cosmic unity through the interplay of feminine and masculine, cosmic and earthly energies, her extensive documentation of the depth her artistic and spiritual process and its meanings has not yet been published.

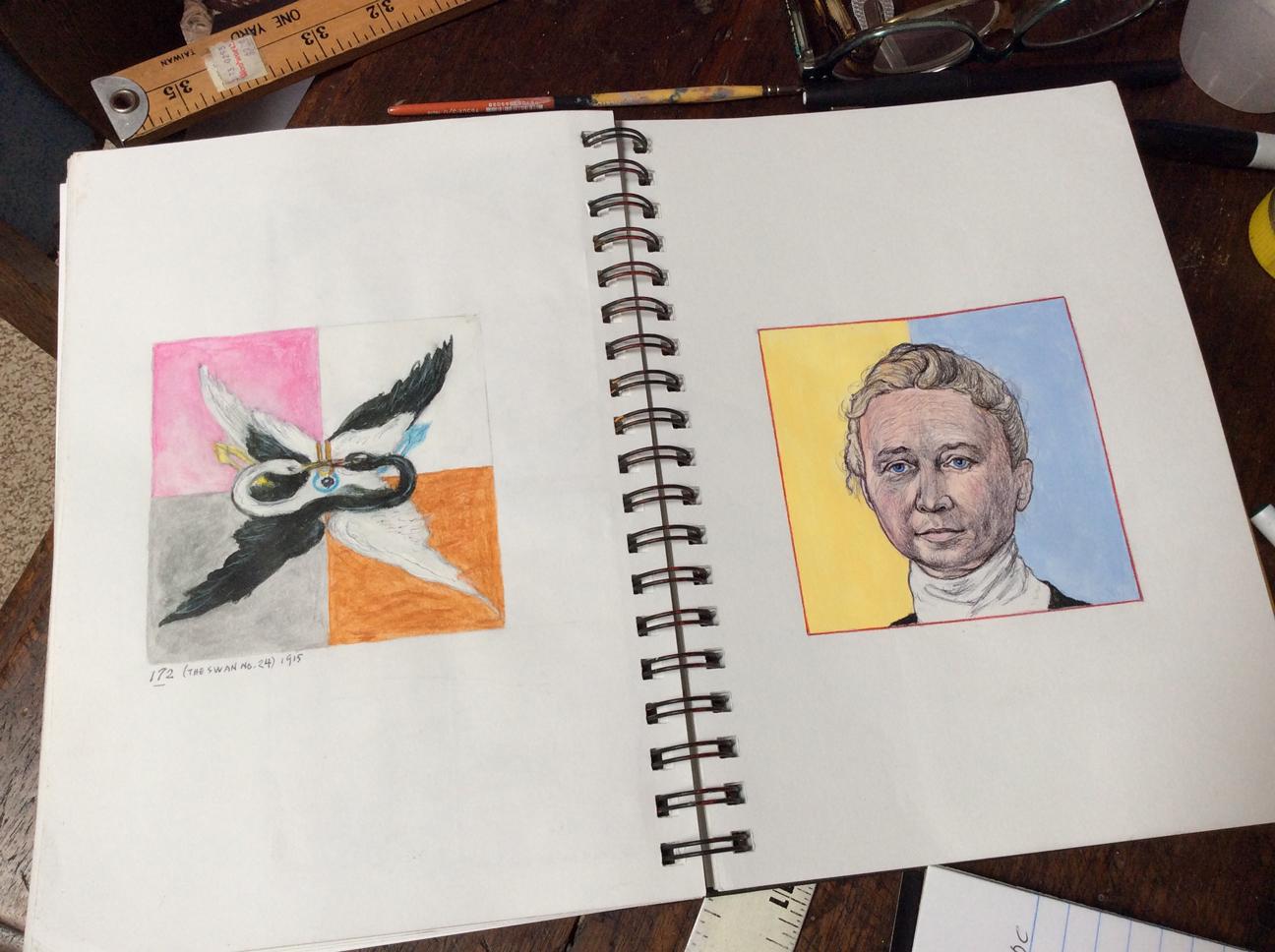

I do not understand her symbolism, but have hoped to gain a view of the mind of the artist by copying a series of paintings known as The Swan, made in 1915. The canvases are 1.5 meters square (her largest works are 240 x 320 cm, nearly 8 by 10 feet). The Swan series begins figurally, explodes into strange vectors and mirroring prismatics followed by the very pure geometry of target-like circles and finally returning to the pair of figural swans, now symbolically interlaced. Af Klint’s line is utterly confident and her often loose painterly technique is masterful. Her art was her most reliable outlet for the philosophical speculation that drove her output of over 1,000 works, that remained mostly hidden until now.

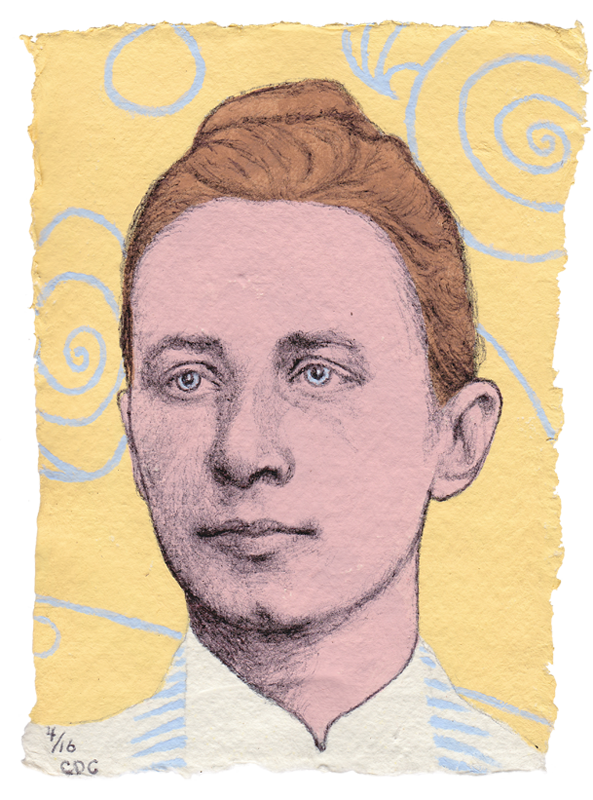

From my journal: copies of Hilma af Klint’s The Swan series, from 1915 and portrait of Hilma af Klint. Media: Flashe vinyl colours, Derwent Inktense water color pencils, Prismacolor, pencil, Bic pen.